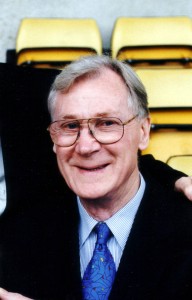

Pure Gold, The Part-Timer Who Won The Lot

By David Instone

What a player, what a life, what a man!

There was, quite simply, so much to William John Slater. His colossal football achievements were nothing like the full story.

He was an absolute one-off; a throwback not so much to a different era but to what in many ways was a different game.

Even his admiring Molineux team-mates marvelled at a schedule that left him unavailable to Stan Cullis much more often than occupational hazards such as injury and suspension would dictate.

In the early years of his Molineux stay of 339 League and cup appearances, Slater was an amateur. When he did turn professional, for the princely signing-on fee of £10, it was on the condition that he could remain as a teacher and would fit training and match days in as best he could around the requirements of the classroom at Birmingham University.

Quite how far he went in retaining this connection with the outside world was spelled out when, en route to report on Steve Bull’s two-goal heroics for England against Czechoslovakia at Wembley, I visited his home in Ealing, West London, to interview him for my 1990 book, Wolverhampton Wanderers Greats.

Two years before the famous Matthews final (the one actually decided by a Stan Mortensen hat-trick), this strapping son of Clitheroe half an hour or so east across Lancashire had played at inside-left in Blackpool’s 1951 defeat at the twin towers against Newcastle. Slater was very much in the rookie phase, in the side because of a spring-time broken leg suffered by Allan Brown – and still in education.

“I was on a PE course in Leeds and unfortunately had to be back up there on the Saturday night,” he told me. “I was on a train packed with celebrating Newcastle supporters when the rest of the Blackpool players were gathering for the banquet. I sent the whole journey sitting in a corner and hiding my face in case I was recognised as a member of the opposition camp.”

Slater’s Bloomfield Road career was restricted to around 30 appearances – laced with nine goals – but they were made in the middle of a remarkable unbroken 30-year stretch as a top-flight club. Blackpool, who signed him in 1944 after he had impressed local scouts, were serious box office at the time. Who wouldn’t be with Matthews on board?

His subsequent stint at Brentford was shorter still. But playing in West London meant Bill could be much closer to girlfriend Marion, who he married a few months later. That stay also provided him with the experience of playing in a Griffin Park half-back line completed by Jimmy Hill and Ron Greenwood.

The end of college life did not mean Slater put down his pen and paper. When chosen for the Great Britain side at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, he was so impressed with the Hungary players who won the gold medal that he wrote a long piece about them for an FA magazine on his return. How well his warnings were heeded is open to debate because the Magyars hammered England 6-3 and 7-1 at senior level over the next year or so.

The young Slater clearly had much about him. When work brought him to the Midlands, he took matters into his own hands by knocking on Cullis’s door in the summer of 1952 to ask for a chance at Wolves.

And it was there that his manners landed him in trouble. His exemplary manners, that is. Politely, he said he didn’t mind which team he played for, as long as he was given a regular game – a comment that led to the Iron Manager having him on the receiving end of a lecture for a change amid the reminder that he should leave immediately unless he had ambitions to play in the First Division.

Cullis’s high hopes for him weren’t unfounded, even if two members of the Wolves board expressed serious reservations about the club signing an amateur.

As at Blackpool, Slater was sometimes used early on as an inside-forward, largely because of the half-back strength present in abundance at Molineux in the shape of Ron Flowers and a quartet of Bills, namely Messrs Baxter, Crook, Wright and Shorthouse.

But he played mainly at right-half when appearing in 39 of the 42 Division One fixtures as Albion were beaten to the title in 1953-54 and he continued racking up the games at a rate which leaves us to wonder just how many outings he would have amassed had he not had to miss some night matches because of his day job.

So keen was Cullis to have him available for one game at Sheffield United that he arranged to fly the player north after lessons had finished. The plan was to have a Don Everall’s driver in place to pick him up but the craft landed at the wrong airfield and a late team change had to be made as the missing man hitch-hiked the rest of the journey.

End-of-season tours, brief Continental trips and even the midweek Charity Shield draw with Albion were other commitments Slater had to pull out of and the emergence of Eddie Clamp made his place less certain when Wolves re-emerged late in the 1950s stronger than ever.

At the end of a triumphant title-winning campaign in which Slater played only 14 League games, the two men, plus Wright, all went and played together in the 1958 World Cup finals, with England so well blessed in that department that they could afford to leave Flowers back at Molineux. Slater was actually hit in the pocket by going to the tournament in Sweden. His university wages were docked and the expenses he received from the FA did not make up the difference.

These were dizzy days indeed. The Championship crown was retained in 1959 and Wolves went within a point of making it three in a row during a season in which they had the huge consolation of lifting the FA Cup.

Billy had by now retired and, with his successor as captain, Eddie Stuart, losing his place in the team in the spring, Slater was made centre-half and skipper. He was a hugely prized member of the playing staff, albeit still part-time.

Not many men play in one FA Cup final as an amateur, in another as a winning captain and participate in both an Olympics and a World Cup finals. But this holder of 12 England caps and 21 amateur caps was a true class act. His record of winning three League titles and one FA Cup makes that abundantly clear.

In the weekend that he went to Wembley with Wolves for the first time – for the comfortable 3-0 victory over a Blackburn side closest to his roots – he was also named Footballer of the Year. You would have to search long and hard to unearth purer gold than this.

Not bad for someone who for several years cost the club no more than train or mileage expenses from Bournville in Birmingham and a turkey at Christmas.

For three more years after Wembley, this time trophy-less ones that led up to a last-day 5-1 hiding at Blackburn, Slater served the Wanderers cause and whole generations of fans who never saw him lace up his boots know he was a star off the field as well.

Among other posts, while or after graduating as a Bachelor of Science, he became deputy director of Crystal Palace sports centre, director of PE at Liverpool and Birmingham Universities, chairman of the West Midlands Sports Council, a paid servant of the National Sports, a member of the National Olympic Committee and president of the British Amateur Gymnastics Association.

In 1982, he was summoned to Buckingham Palace to receive the OBE from The Queen and a CBE followed 16 years later, again for services to sport.

There are other less well-known strands to the rich tapestry. He coached daughter Barbara when she qualified and went to the Montreal Olympics as part of our gymnastics team in 1976, mother Marion setting foot on a plane for the first time when she went to Canada to watch.

Barbara, a long-time director of BBC Sport, was born a couple of weeks after Wolves retained their Championship crown in 1976 and it is through football achievements that we will of course best remember her father.

As well as being the last amateur to appear in the Cup Final and the oldest surviving Wolves player up to his death from Alzheimer’s on Tuesday, Slater has a place in Wolves’ Hall of Fame and has only 23 men ahead of him in the club’s all-time record appearance-makers list.

He was known throughout the game as a man of virtue and fair play – and the TV cameras picked up his obvious displeasure when Ted Farmer celebrated a Wolves goal against Manchester City by gloating over the prostrate body of goalkeeper Bert Trautmann.

My own fond memories of Bill include his cheerful, unfailingly polite and appreciative appearances at Molineux dinners and book launches, for which he usually arrived first after a sprightly walk from the railway station.

A day or two before I and a camera crew were due at his house more than a decade ago to film and interview him for the official History of Wolves dvd, he rang to ask if we could see him at Molineux instead, so he could pop along and see mates from his playing days.

At a 1963 dinner in his honour at Wolverhampton’s Victoria Hotel, Stan Cullis said: “I know of no-one who created a greater impact on the players at Molineux than Bill – with his self-discipline, good behaviour and sportsmanship. I wish we had many more like him.”