A Family Rich In Football Folklore

How many more games might Jimmy Dunn have played for Wolves? First, the war took much potential match time away from him, in terms of Football League action anyway, then a bad injury and finally any number of outstanding fellow forwards.

His appearance tally is a substantial but unremarkable 144 but the 40 goals with which he decorated those outings underline the point that he was an impressive performer at Molineux; very much one of those who got the club rolling towards their 1950s greatness.

The highlight of his career was undoubtedly the 1948-49 FA Cup journey. He played in all seven games in the triumphant run, netting for the second successive round when he faced Liverpool at home in the last 16 and being part of the side who prevailed in a Goodison Park replay to a stirring semi-final against the holders Manchester United.

With Dunn’s passing-away yesterday at the age of 91 and that of the even older Bert Williams early in 2014, we are now left with the unwell Sammy Smyth as the sole survivor of the Wolves side who defeated Leicester at Wembley 66 seasons ago.

It’s a sad fact but at least, with Bill Crook and Bill Shorthouse not being lost until their mid-80s, the team have been blessed with long life. Smyth turns 90 next month, so the Wolves family have something to be thankful for. Albion, by comparison, said farewell as long ago as March, 2012, to the last survivor (Ray Barlow) of the line-up who won the FA Cup in 1954 just after finishing as runners-up in the League to Stan Cullis’s men.

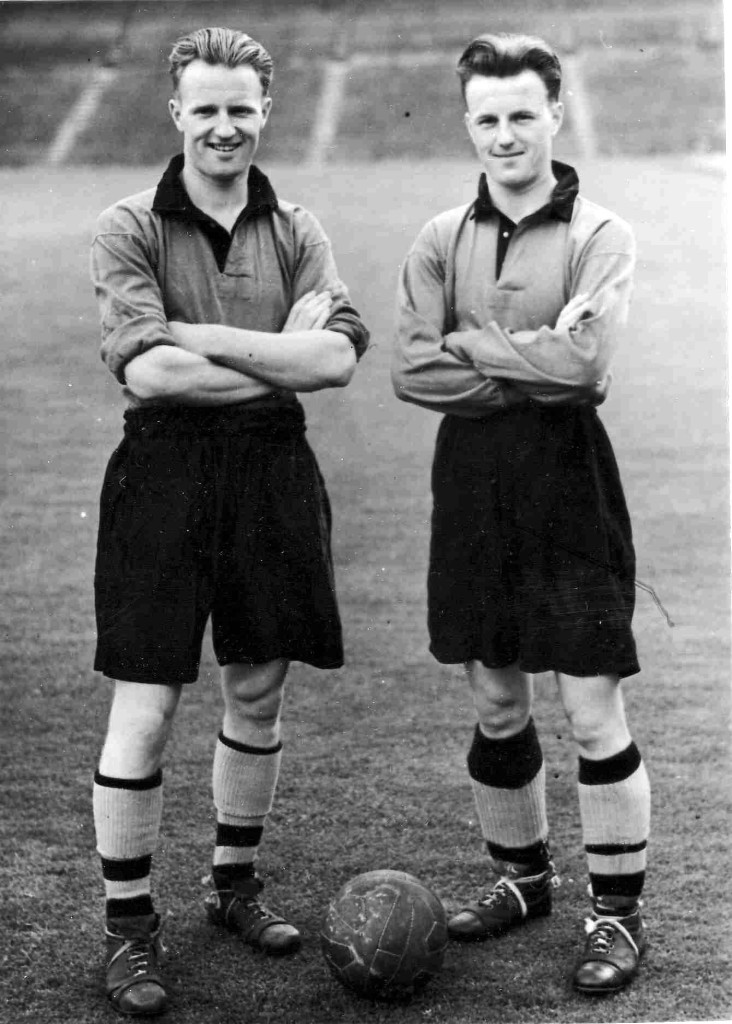

Those Merseyside connections on the Cup trail were highly significant to Jimmy Dunn. Although born in Edinburgh, he was brought up among Liverpool and Everton fans as his father, also Jimmy, had played for the blue half for seven years after serving Hibernian and achieving fame as one of the ‘Wembley Wizards’ – the tiny Scotland forward line who mesmerised England in a 5-1 victory south of the border in 1928.

James Jnr, so named because he was born on his dad’s birthday, was much more Scouse than Lothian to speak to, a cheeky chappie who giggled as he once recounted how ‘me old man’ had thrown a fellow passenger off a bus when he heard him criticising the performance of the Wolves inside-forward on the ride home from that day’s game.

He worried for a while about whether he would face Leicester at the twin towers in 1949. Dennis Wilshaw had made an astonishing arrival in the side before and after semi-final match-winner Jesse Pye had gone absent for several weeks through injury, so Dunn and Smyth each feared they might be sacrificed if the senior man recovered in time.

Cullis eventually left out the uncomplaining Wilshaw and the afternoon’s events proved his judgement correct against the lowly Second Division underdogs. Pye, who Dunn revealed as a ‘character’ who placed a match and half-cigarette in his shorts so he could nip for a smoke in the toilet on the way in at half-time and full-time, scored twice. Smyth got the other with a memorable solo effort while Dunn was screaming for a pass and destined to suffer the slight disappointment of failing to match his father’s feat of scoring in the 1933 final – for Everton against Manchester City.

Football, like the country as a whole, was still readjusting to peacetime as Wolves, following their pre-war near misses, were winning their first major honour for 31 years.

League football hadn’t resumed until 1946-47, the opening day of which saw Pye net a hat-trick in a 6-1 slaughter of Arsenal on an afternoon also marked by the First Division debuts of Williams, Billy Wright and Johnny Hancocks.

At that time, Dunn was on the outside looking in despite having arrived at Molineux as an amateur in 1941 during the Major Frank Buckley reign. He played more than 100 wartime games for the club and doubled up as a railway fireman, one Friday night shift taking him past Bolton’s Burnden Park ground a few hours before he went back to play there.

With Dennis Westcott still in his pomp, he had to be patient for the big breakthrough, which came with his 28 games and nine goals under the management of Ted Vizard in 1947-48.

He improved on that appearance total in the Cup-winning season and was said to have been under consideration for emulating his six-times-capped father by gaining Scotland recognition of his own until he suffered a back injury that required an operation and meant he didn’t play after October in 1949-50.

Happily, he made a full enough recovery as to be flying the following year and helping Wolves to another semi-final with four Cup goals in his best Molineux season. Then came two important lessons, the first provided by defeat in a replay against Newcastle at Huddersfield, where he was to score a League hat-trick five months later.

So convinced was he that another Wembley visit was imminent that he had buyers lined up for his allocation of Cup final tickets – a recognised but frowned-upon perk for players who were then on around £12 a week, with £2 win bonuses. Wolves, unluckily, went out at the last-four stage by the odd goal.

When I interviewed Jimmy for my Wolves: The Glory Years book in 2005, he opened up about his relationship with the ‘Iron Manager’ and revealed one possible breaking point.

“I got on really well with Stan,” he said. “At one stage, he thought my physique needed building up, so he arranged with a local butcher, who was a Wolves supporter, to deliver 2lbs of steak to me every Friday.

“As long as he saw you doing your damnedest, he would pretty much leave you alone but he couldn’t stand a non-trier. He only had a go at me the once – just before the end of 1950-51 when we were playing on a hard, bouncy surface at Molineux. We had a tour of South Africa coming up a couple of weeks later and I was looking very much to that, so I didn’t want to get injured again.

“In the first half, the full-back came across from my side for a 50-50 ball and I shirked the challenge. It didn’t escape Stan’s attention and, at half-time, he made a bee-line for me and said: ‘I know what’s in your mind but if you do that again, you won’t be playing for me any more.’ It certainly taught me a lesson.”

Dunn, whose brother Tommy was briefly on Wolves’ books, played another 26 games in 1951-52 but the young Peter Broadbent and Roy Swinbourne were emerging, in addition to Wilshaw, and he was sold to Derby for £20,000 the following season.

Although East Midlands sources record the outlay as £15,000, it was a considerable fee for the era. The player scored on his debut – a more than happy occasion as it was a 3-2 home win over Liverpool – but the Rams, who subsequently recruited Pye and another man with Molineux connections, Frank Upton, were heading for relegation from the top flight.

Dunn suffered further injury misfortune, this time with a cartilage problem, so his total of 21 goals in 58 games for the club was more than respectable before he dropped into non-League with Worcester and Runcorn.

A succession of jobs followed, including those of physio, gym boss and rep, even as landlord of The Roebuck pub in Penn. His lengthy time as Albion trainer and physio in the 1960s included an FA Youth Cup final turnaround to rival that of the famous Wolves-Chelsea spectacular more than a decade earlier.

Working with a talented 1968-69 squad containing Alistair Robertson, he was left picking young chins up off the floor after a 3-0 home win in the Hawthorns home leg was followed by a 6-0 crash in the return at Sunderland, where Asa Hartford and Jim Holton were sent off.

We at Wolves Heroes made the last of a handful of visits to Jimmy’s home just off the Old Hill-to-Halesowen road five years ago this month. Please type ‘Dunn Merseyside epics’ (without the quote marks) into the search engine above right if you wish to revisit that story now. He had not long lost his wife and would later spend time in the same Bilston care home as Bert Williams.

He was always good, lively company – and was clearly some player as well.